Continue to Live

by Oliver Zarandi

My entire family died over one weekend. Perished. There was mom, dad, my sisters, my brothers, my aunt, my uncle, my grandma on dad’s side, a great uncle who wasn’t so great and was, in fact, a parasite, and two dogs, both called “Barney” — the quote marks being a part of their names.

So Tobias and I had plenty to be stressed about. The flesh-eating virus that had ravaged half the country was finally in our state.

He was loading the car up with the essentials. His head looked like a lasagne. It always looks like some sort of pasta dish when he’s stressed. He was basically layers of egg, cheese and beef.

I watched Tobias load blankets and clothes into the back of the car. Tobias loved me. His love was big and fat and always hard. His love made a mess and you’d have to clean it up with a rag. Jesus, I’m so sorry, he’d say, all sheepish. I gone got my love everywhere again!

He loved me so much that he bought me flowers every day for the past five years. Sometimes before bed, he’d get down on his knees and serenade me to sleep. Other times he’d leave small love poems in my pockets that I’d unearth at work — Shelley, Byron, the Romantics — then follow up with a text: Did you get my note? 🙂

He loved me with all his heart.

But before we move on, I’d like to say this: There’s something wrong with me.

I like to trace my wrongness in this little timeline of events, like the ones you get in history books. 1993, just says eating disorder. 1994, The Year Of Hiding Food Down The Back Of Radiators. 1995 — the year I fell in love with Val Kilmer’s lips. I’d dream of his lips in Tombstone and Batman Forever, floating around my room, smooching at the air. And then there was 2006, the year I had surgery. My mom, dead now, said my surgery was a gory one, reminiscent of something in a butcher’s shop.

You were like a prized beef, Gilda, she said stroking my limp hair. Apparently they’d sliced and diced me, taken something out of me, put me back together again.

Limp-haired Gilda, said my mom, like she was soothing her beloved basset hound.

She visited me every day, and it wasn’t unpleasant, let’s put it that way. But just next to us was this porridge-skinned elderly man, arms like two limp dicks, hanging down the side of his bed.

Mom, I said, is that man okay?

Who? This one? He’s fine. He’s had his heart replaced.

The wonders of modern medicine. I wondered whose heart it was. I wanted to grab the doctors by the lapels and in my finest Jack Nicholson impression ask them: Doc, who’d ya put inside the old man? Djoo plop a cow heart in him, sew him back up? Tell me!

For days, I watched the old man continue to live, all thanks to this alien heart. Maybe it was the heart of a dead kid. Maybe the kid was murdered and the old man would get a new lease of life, from the life that’d been ripped from this kid. Wow, I thought. Humanity!

But it didn’t last. One night the old man woke me up, coughing his guts out. His body was rejecting the heart. After around 15 minutes, he had completely jettisoned all life from his vessel.

I thought about the old man for a while, about who he was, about his own heart, where that went, and the new heart, where that was from, and how unique he was. Not many of us get to have two hearts in one lifetime. But his body didn’t want that new heart.

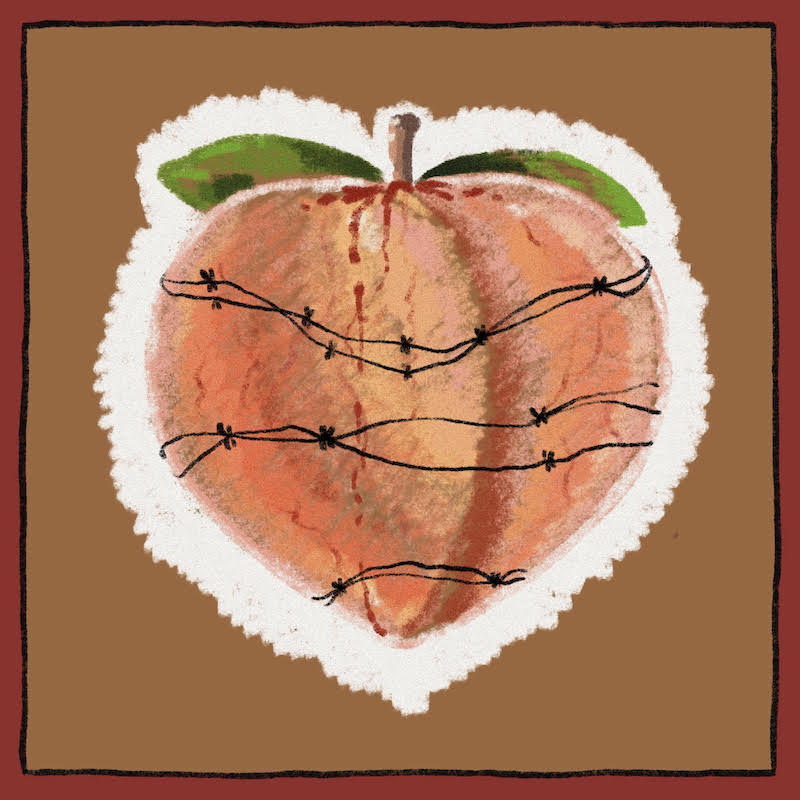

And this is the problem I have with Tobias—I don’t love him.

In fact, I hate him.

I find that my body rejects all good things in life. When Tobias touches me, I want to vomit. Or at least, I want to scour myself thoroughly with a metal pad.

I am incapable of enjoying beautiful places, too. I’m a hog for squalor and a shit time.

Tobias loaded the last box into the crapped out station wagon and whistled for me to get in. I did.

Apparently I was making a face because when Tobias got in and put his seatbelt on, he stared over at me, sighed, slapped both hands on the steering wheel, bracing himself for what he was about to say and turned to me.

Look, it’s for a few weeks. Just until this blows over.

It won’t blow over. It’s eaten half my family.

And I’m grieving. I really am. But we need to look out for number one.

Right.

Okay?

Yeah. Okay. But…

But?

But we should be with our fellow human beings during this. Why leave the inferno, Tobias?

It was true: a part of me wanted to stay, to fight it out. But then I thought of how the virus had got my Uncle Joseph, had infected his leg and started rotting his flesh down. We saw the pictures. His leg looked like wet bread. The skin came straight off like a condom.

Tobias laughed at my comment. He shook his head, started the car, reversed out the driveway and drove into town. As we passed through, we could see people inside their homes.

I rolled down the window and shouted, GOOD LUCK, GOOD LUCK!

Hey, Tobias said, what the fuck?

I’m wishing the soon-to-be-dead good luck.

Well, don’t.

I folded my arms and slumped down into my seat. I didn’t want to reach our destination. I wanted to get to a gas station and ask somebody to kidnap me. Maybe they could take me to Las Vegas? Somewhere off Fremont Street with free HBO, free porn, drink tequila shots and shit myself, make friends with bums and junkies?

Rain started to hammer the car. Tobias leaned forward and tried to squint through the window.

I might have to pull over, you know, he said.

Don’t. We’re nearly there.

No we’re not. We’ve got another 15 hours.

I turned on the radio and watched the spermy raindrops wriggle down the window. One of the slower raindrops reminded me of Tobias and how he didn’t come to the funeral, how he painted a huge family portrait for me instead. Funerals make me so damn sad, he said. But I’ll be there for you. In spirit. And hopefully this painting will remind you of all their beautiful faces.

In spirit.

My eyes changed focus and just ahead there was a figure in the distance, standing in the rain, his thumb sticking out.

Tobias, a hitchhiker. Can we?

What? No. Who does that?

We do. He’s out in the middle of nowhere. Come on.

I don’t know.

Please. Please!

Fine, fine. But you can keep them company.

We pulled up to the side of the road. I rolled down the window and the man walked over to us. He was young and soggy.

Where you headed, amigo? said Tobias.

Why’d he say it this way? Like he was in a Western. I was humiliated.

Anywhere north of here. I just need to get down the road some. As far as you can.

Tobias looked at me. I looked at Tobias. Tobias looked at the man and nodded his fat lasagne head.

Take them clothes off first, pardner, he said.

What’s that? said the hitchhiker.

Your clothes. We need to see if you got the markings.

The hitchhiker stared at us both for a second. Then he took a breath and started peeling his clothes off. When he was completely naked, he covered his penis with his hands. His skin reminded me of a white plastic bag. Tobias told him to turn around so we could look for sores. That was one of the ways you knew early on—paisley-patterned sores that opened up all over your body.

You can put them clothes back on now, pardner! said Tobias.

The young man got in the back, his wet clothes squelching on the leather seats.

What’s your name?

I’m Oates.

Well, I’m Gilda. And this is Tobias.

Thank you for, uh, stopping.

It’s no bother, pardner, said Tobias.

You’d be surprised how many people don’t stop.

Not really, I said. There’s a virus. It’s natural people aren’t stopping.

I turned around to try and engage. It’d be rude not to.

Oates nodded. He had red cheeks and yellow teeth and looked like somebody who was raised on Jesus and sex abuse. If I had to guess his occupation, it’d be fisherman. He wore a too-big striped shirt, and kept his small and pale hands folded in his lap. He caught me looking and put his hands in his pockets.

You folks running from the virus?

We’re just out getting some alone time, I said. Wait until everything blows over.

It won’t blow over.

Optimistic boy, ain’t you, Tobias said in his weird John Wayne accent. He was like this with people he thought were poor. A yokel accent or Western drawl, as if this would put them on a level playing field.

Oates just smiled, didn’t blink. He brought his small, pale hands back out, put them out on his knees and gave me a quick, yellow smile. In my mind, I hoped that Oates would murder Tobias, or at least severely injure him, and kidnap me. I hoped, I wished!

It was dark and the rain wouldn’t stop, so when Tobias saw the white cross, he pulled in. It was a “safe” motel and as we drove up, two men came out with their masks on and asked us to get out of the car. They waved guns at us and said it was all procedure, nothing to worry about. I loved it. I was about ready to come when they asked us to take our clothes off and show our bodies. Tobias looked like a sack of oranges.

We got the okay and drove on up.

The motel was cheap and simple. Oates couldn’t afford his own room, so Tobias paid for one. Oates didn’t have much on him except for a backpack, which he put on his front.

Why on your front? I asked him.

He stared at me again without blinking. It was like my words didn’t register, that I was some distant star and Oates was earth, my light reaching him years later.

Uh, it’s very important to me, he said finally. Then he walked off towards his door, and we walked towards ours. I turned around and Oates was waiting for us to enter our room first.

Tobias felt bad and called out to Oates: Say, pardner—would you like to have dinner with us?

Oates looked down at his hands, like they were cue cards or something. He only focused on his hands, caressing them. Had I angered him? Was his insecurity about his hands so acute that even by me looking at them, I’d set something off in him?

Sure, he said. Yeah, I could eat.

Great, said Tobias. We’re just going to wash. See you here in a few minutes?

Oates nodded. We came back out after thirty minutes or so and Oates looked like he hadn’t moved. The good nature of Tobias had frozen him into a statue.

We walked over in silence to a small “family owned” restaurant. There weren’t that many people in there, just a few elderly people, slowly chewing their food, staring through time. We were ushered by a lardy waitress to a small booth where we scanned the menus without talking. For some reason all language had been sucked out of the cock of us and was just swilling around in the atmosphere’s mouth.

It was only when the waitress returned that we blurted out some words. She nodded, repeated the order back to us and we nodded—yes, yes, yes, and that was that.

We ate in silence too. Oates stared at his food and started organising it into different areas on the plate. He pushed the potatoes into the top left and created a sort of moat with the sauce around it. Clearly he didn’t want the potatoes escaping or the undercooked vegetables invading their space. He put a forkful of food into his mouth and chewed in a way that wasn’t like his jaw was chewing it at all, but his entire head—temples, scalp, and ears. Like he was chewing and swallowing his own cheeks. I couldn’t stop staring.

We returned to the motel. Oates thanked us for the food and put his hand out. Were we meant to shake it? We didn’t know, and besides—he withdrew his hand within seconds.

Thanks again, he said. Thank you very much. For everything. Then he tilted his head and stared at us for a second longer without blinking.

You’re good, pardner, said Tobias, and tipped an invisible cowboy hat to him.

Tobias and I went back to our room and got into bed. We were, as he would constantly say to friends, “bushed”. I lay on top of the covers like a slab of granite as Tobias tucked himself in beside me. I turned over and thought that if my life were a novel, it’d be by As I Lay Sighing by William Faulkner. Come back from the dead, William! Write my life the way it needs to be written.

Tobias turned over and kissed my right cheek.

God, I love your cheeks, he said. Do you know I thank god for your cheeks?

That’s sweet.

He pinched my cheek and chuckled ‘Tee hee!’

And I love your jugs. I thank god for your jugs.

I know.

They’re so big and motherly. He nestled his head up to my right breast and kissed it. Then his head retreated back and he turned his face upwards to the oily ceiling and went pale. He always looked like he was dying when he fell asleep.

I kept my eyes closed too. I tried focusing on my heart, its rhythm, its beating. All that blood going around my body. Doesn’t it get bored? I guess not. Blood doesn’t get bored, but it does get agitated. Like the old man with the murdered child’s heart, or the cow heart, whatever they put in him. I had the strangest image of the old man’s arteries filling with Lemmings, those little green mop-haired fucks from that computer game, and they were all wandering around going in different directions, bumping into piles of plaque. Imagine having that inside of you! I wondered if somebody would have to give me a new heart one day. What kind of heart would it be?

My thoughts were interrupted by a small chiseling sound. Somebody is trying to break into the room, I thought. Yet I kept my eyes closed. I waited. Don’t open your eyes, I whispered. Why fight it? Why bother?

Then the door creaked open and I opened my eyes enough to see that Oates had entered the room.

He stood there in the darkness of our room, breathing in and out. It was like his lungs were horny for the air in the room. Then he took his shoes off and placed them delicately by the door. He walked around a little on the carpet to test if he was loud or not. I was ready to run, to get in the car and drive off from both of them. But I didn’t. I didn’t move. I wanted to see what Oates wanted.

He shuffled over and sat on the end of our bed. I could hear him breathing harder now. And I felt his tiny child hand on my thigh. It was clammy. Then he moved it over to Tobias. I moved my head to see what was going on, taking care to make sure Oates didn’t know I was awake. Now his hand palmed Tobias’s face. He was stroking it. Tobias didn’t wake. Of course not. Oates could’ve fired off a gun into the ceiling if he wanted. I watched his pale, milky fingers stroking Tobias’s pale waxen face—back and forth, back and forth.

Then Oates pulled his own trousers down. I couldn’t see his penis, but I could tell what he was holding. I could smell it. He was moved both hands in time, getting faster and faster. It was a feat of coordination, like those people who can pat their heads and rub their belly in a circular motion.

Oates shuddered. I shuddered too. That was his love leaving his body onto our carpet. And then he fell silent again, like he wasn’t alive at all, but just some ghoul hovering in our room.

My eyes opened and Oates was staring directly into them. He pulled out a knife from his bag on the floor, held it to Tobias’s throat and raised his creamed-on finger to his lips so I wouldn’t say a word.

I winked back at him. I felt like a new heart had been placed inside of me. It was filled with love and I wished him all the best.