CHEAP NIGHT

by Garielle Lutz

I was eventually sent off to a number of different people, a second round of specialists, about everything else that was said to have still not been set right. One was a man with an office on a sliver of a street in what was left of the business district. He had me sit in an anteroom with him while he filled out the first of the forms without ever looking over at me. Then I followed him into the better room, where there was a desk. On a sheet of a tablet that had been printed to look like a prescription pad, he wrote down the name of a woman who he said cut hair in ways that helped people along.

The appointment was for seven that evening.

This was a tall, damp-looking woman in a smock. She asked no questions. She set my head backward into a narrow sink for a hurried, turbulent shampoo. Once her fingers got moving across my scalp, she barged a portion of her limited side-flesh informally against my shoulder bone. The result was maybe some useless, cradlesong warmth—nothing more, I am sorry to report. The next thing she did was seesaw a towel back and forth across my skull, then tug me toward the barber chair and wrap me in a sheet. It was a routine haircut after that, I guess, until she pressed her palm against my cheek. She kept the hand there, detained it professionally, as it were, until the skin heated up. Whether it was departing heat of mine or a transfer of hers I could not at the time decide, but here I had the handicap of a wall before me that was solid mirror, and in going wide of my own reflection, I could not help unpiecing the woman’s face into, first, a powdered-over replica of the large-pored, forthcoming nose of the specialist who had referred me there, and a chin of his own depthlessness (though here again given cosmeticized redefinition), and his wide-set, shittily brown eyes.

I muttered something about nepotism, kickbacks, etc., tore myself free of the sheet, stormed out.

At a pay phone, I called my only friend, a very good acquaintance of mine, someone I hardly knew enough to think of except at times like this. He said he had right that very instant finished ruining an hour in an adult-book store with an invalid video machine and a man suffering love-cramps of his own.

This friend said he wasn’t up for getting together.

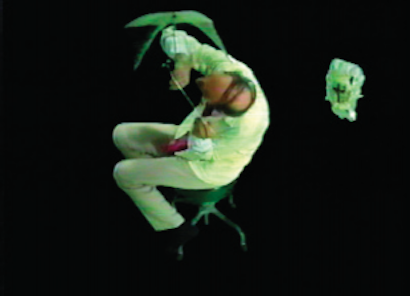

On my way home, what the hell, I stopped off at my stepsister’s. I found her in the living room, her arms spired above her head in a shortcut rendition of an exercise some woman was enacting on the silenced TV.

My stepsister was in trunks, baggy socks, an undershirt. She struck me as no more than an enlargement of her scowly daughter on the sofa. I compiled myself onto one of the baggier side chairs. From this privileged elevation I watched my stepsister, now down on the hardwood floor, bucking around on her stomach, raising her rear to a resultful summit—not a push-up exactly.

It was the daughter’s idea that the three of us should go out for a bite to eat. “Unless you’d not rather,” she said to her mother. Her mother said she’d tag along. We drove in the daughter’s car to a below-stairs eating place she knew. Running the length of the wall facing the street was a band of windows that took detailed notice of the lower legs of passersby—skirts of coats, slow-going feet of people coping.

The daughter called our attention to a blemish on her left cheek, a little pink difference. She kept her fingers on it, twiddling at it, kneading away at her cheek, until the disturbance itself seemed to vanish into the environing complexion. Then she took her hand away, and the blemish reappeared with a renewed sickliness.

“But catch me up about you,” she said.

I guess I was a kind of handy, convenient mystery to her, and every fact I gave her had an efficient way of instantly separating itself from any larger certitude. I have never liked feeling a point of view being trained on me too sharply.

My stepsister motioned toward the arrowy sign that pointed to the restrooms, then got up, taking her handbag and jacket. The daughter mentioned having seen an old teacher of hers faking a vacation in a chaise longue one neighborhood over. She spoke of little shares of chocolate she had once arranged and rearranged until they were practically mush and had to be licked off her fingers by more than just one lonesome mouth but her boyfriend was nowhere to be found. She’d had to recruit a girl she knew from the public pool who kept perfecting more and more ways of looking marooned. And this daughter said she could no longer feel any connection to lengthier and lengthier spans of her life. They no longer seemed hers to have lived through. She claimed she did not so much crawl out of her bed in the morning as originate anew from it.

I felt threats already piling up behind everything she said.

“Blow into my life,” she said.

My stepsister returned to our table, settled in.

I was looking out of my face at the two of them. I could feel the holes I was looking out at them through. Everything looked rimmed and rounded around. My body must have been sitting behind me or just to the side. The two of me did not quite coincide.

“You have this responsibility,” she said.

Garielle Lutz’s new short-story collection, Worsted, is forthcoming from Short Flight/Long Drive Books.