Adult Education

Brandi Handley

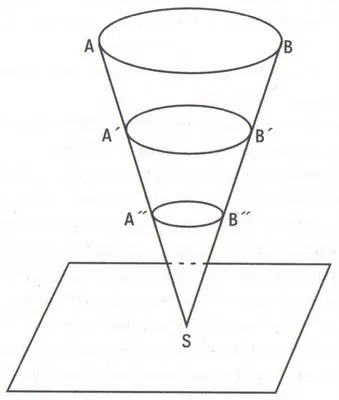

After a good fifteen minutes, Hailey and I are still stuck on a volume problem. Find the volume of the cube. This should be an easy question—just plug the numbers into the formula. But the answer she and I keep coming up with does not match the answer in the back of the book. I immediately think: typo. The book is wrong; we are right.

Hailey is a twenty-four-year-old student so close to taking the high school equivalency test that she’s made it to geometry. Frankly, she’s a lot better at math than I am. She’s figuring numbers in her head while I’m writing them out on paper.

The Big Q Quik Trip cup, purse full of snacks, and extra pencils mean she’s in it for the long haul. And as I scan the classroom for the other teacher to help us, she keeps studying the volume problem.

“Oh!” Hailey says. “That’s what it is.”

“What,” I say, “what did we miss?”

“The width is in feet, the length and height are in inches,” she says. “We have to convert the feet to inches.”

I look at the cube in her math book. Sure enough, the width is in feet. How either of us missed such an obvious step seems incredible. One little bump and we’d been derailed.

Jim is in his sixties and hasn’t sat inside a classroom in more than forty years, having spent those years driving an eighteen-wheeler. He wants to drive school buses so he can spend more time at home with his family. Even with all of his experience, he cannot apply for a position without a high school equivalency certificate. Tonight is his first class with us and in preparation he has brought his own pencil and a pair of reading glasses that he keeps in a leather pouch in his breast pocket.

Like Hailey, he has strong math skills—while we start most students on fractions, we start Jim on geometry. He and Hailey should pass the math portion of the high school equivalency test in a matter of weeks.

He sips from a water bottle throughout the class period, making sure it lasts all three hours. At the end of class he says, “If I’d known it was this easy, I’d’ve done it a long time ago.”

While math comes relatively easy to Jim and Hailey, it is Kryptonite to a lot of students. Joanna enrolled in our program once before but quit amid a battle with fractions, a derailment that lasted several years. She’s returned with an infectious positive attitude and a package of Jesus pencils.

Tonight she places the pencils on the table in front of her. They say things like, “I ♥ Jesus” and “Jesus makes it possible!” She says that she’s not only brought her Jesus pencils, she’s brought the man himself. “I got Jesus with me. He’s going to get me through this.”

Rebecca, like the other students, does not have a high school diploma, yet she’s a loan officer at a small bank. She dresses in button down shirts, slacks, and flats. Her hair is short and straight, and a brown barrette fastens it away from her face. She arranges her student folder, notebook paper, and pencils neatly on her desk. Her work is meticulous. She asks questions. She listens. And she has failed the math portion of the high school equivalency test five times.

She’s tried high school equivalency classes before, years ago, and just recently online classes, which have helped her pass reading, science, social studies, and writing. Only math remains. She wonders why she can do algebra in class but not on the test.

; This evening she sits tightly wound at her desk, her shoulders tensed up to her ears. “I don’t know what I’ll do if I fail again,” she says. She’s been with us five months already and has been one point away from passing, but on her latest attempt her score dropped severely, though she’d studied harder. She has one more attempt left for this calendar year.

Next to Rebecca sits Laurie, who carries a Hello Kitty backpack and wears glittery barrettes in her spiral-curled bob. She’s 43—the same age as Rebecca. This is her first attempt at classes of any kind since she dropped out of school more than twenty-five years ago. She struggles with fractions, percents, and long division. But she’s decided to go ahead and take the math portion of the test, just to see what it’s like.

We marvel when she passes on her first try.

“Imma good guesser,” she says.

When I started at the adult education program, I’d never taught before and wasn’t sure I wanted to. But the program needed another teacher and I needed a part-time job while I pursued graduate school. At 5:45 in the evening, Debbie, a teacher in the program, gave me the grand tour of the facilities—the bathrooms, the water fountain, the classroom where students had started to arrive.

They signed in on a small table, picked a yellow or Halloween-themed pencil from a basket, and pulled their student folders from a filing cabinet. I didn’t hear any greetings or excited chatter like one might hear in a high school classroom. Most of the students had come from a job or their children. A couple of younger students, maybe seventeen or eighteen years old, appeared as if they’d just rolled out of bed, looking as tired as the others. The classroom got crowded and warm in a hurry.

The first hour of class was independent study. Students worked on assignments that addressed their individual weaknesses, while two teachers went from student to student answering questions and explaining concepts one-on-one.

I watched from beneath an array of educational posters diagramming a plant and animal cell, the parts of a flower, and the solar system; detailing decimals, fractions, and the multiplication table; and listing grammar rules and the writing process (pre-write, draft, proofread, share). A globe, a world map, and a map of the U. S. were all at least fifteen years out of date. There were books—textbooks of every school subject, dictionaries with faded red covers held together at the spine with masking tape, and exercise books with yellowed pages and 1970s copyright dates.

An entire public education—kindergarten through twelfth grade—was crammed into that one classroom. The weight of it hung there, palpable. I went out into the lobby to get some air, afraid a student might ask me to explain photosynthesis or algebra. At that point, I wasn’t sure I could explain long division.

As the first hour of class came to an end, so did my time as an observer. The second hour was a group lesson. “You can help me teach the lesson tonight,” said Debbie. “You were an English major, right?”

I nodded. Maybe helping meant passing out worksheets.

“You can do an essay lesson. You want to?”

“Uh, sure,” I said. I followed her to the director’s office where she Googled five-paragraph essay graphic organizers.

“How about this one?” she said, mousing over one shaped as a hamburger. The two buns symbolized the introduction and conclusion paragraphs; the lettuce, tomato, and hamburger patty symbolized the three body paragraphs in between (or the “meat” of the essay). “This one’s easy for people to remember,” she said. “We have to keep things simple for this crowd.”

Then Debbie said, “If you could be a cartoon character or a super hero, who would you be?”

I tensed up at the question. Betty Boop randomly came to mind and the Powerpuff Girls. Finally, I said, “Bugs Bunny?”

“Why?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, hurry and think of three reasons. That’s the essay question we’re going to give the class.” She handed me the stack of freshly printed hamburger graphic organizers. “You can show the class how to use these with your example.”

I stood in front of the class, a roomful of adults—people I’d soon come to know as mothers, fathers, certified nursing assistants, managers, bank tellers, factory workers—and drew a giant hamburger on the board so I could explain why I wanted to be Bugs Bunny.

The simplicity of my essay lesson seemed inappropriate in light of the high stakes these students were facing. “This crowd” and the experiences that brought them to our classroom were anything but simple. I found Debbie’s attitude to be common, equating adult education student with drop-out.

In our classroom, hands go up like smoke signals. They hang in the air silently betraying the urgency with which they were sent up. Most students in our program would rather do almost anything than ask a teacher for help. They’ve been in school before and were not successful. They’re skeptical of success now.

But after a few classes, some of the students start to relax and trust us with their questions. On one particularly crowded evening, smoke signals have turned into flares. Hands shoot upward and an inexplicable anxiety shrouds the room.

Steven’s forgotten how to find a common denominator; Nicole is trying to remember if the formula for figuring percents is IS over OF or OF over IS. Carlos needs a hand grading his practice test. Jeremy has been staring at a blank piece of notebook paper for twenty minutes trying to write an essay. Not knowing the multiplication table has stalled Keisha’s progress in fractions. I quickly show her the finger trick for remembering the multiples of nine and give her a handout for the rest.

A few people working on fractions try to help each other until I can get back around to them. Meanwhile, the students at a table across the room are flagging me down to settle a dispute over comma use. I dread that table; I can’t even remember the rules for comma use. I ignore them for a moment to help Maria on sentence formation. I kneel next to her table to get a better view of the exercise. She says, “Honey, you’re too pretty to be on your knees.”

By the time the first hour of class is over, I am almost relieved to be teaching the group lesson. I teach a short one on ratio and proportion. Most of the class is getting it. This is a major victory for both me and the students. The anxiety that has plagued us this evening begins to dissipate. We ease up on ourselves. We crack a smile. Small victories are what keep us coming back.

I have less success teaching essay writing. We’ve whittled down the writing process to what’s listed on the poster stuck to the wall: pre-write, draft, proofread, share. I become a writing drill sergeant:

“Write simple sentences. Don’t be fancy.”

“Only use words that you know how to spell.”

“The essay test is not the time to experiment with punctuation.”

“Stop trying to use semicolons.”

“Lie if you have to—just make sure you answer the question.”

“They are only going to spend two minutes grading your essay, so get to the point.”

I am trying to dispel the mystery of writing, give them rules that are easy to follow. In the process I feel I am dispelling any creativity they may have had, or worse, the desire to keep trying.

More than half of our students stop showing up to class within a month. When each new month rolls around, twenty to thirty more people sign up for orientation. Hundreds of people in Blue Springs, Missouri live and work without a high school diploma.

Blue Springs is a suburb twenty miles east of downtown Kansas City—drive past the business district, 18th and Vine, and Arrowhead and Kauffman stadiums, through Raytown and Independence, and you’re there. It’s a city of 50,000 middle-class Midwesterners. And it’s home to thirteen elementary schools, four middle schools, one freshman center, two high schools—and one alternative school, which houses the Blue Springs Adult Education and Literacy (AEL) program.

The alternative school was formerly Hall-McCarter Middle School. My middle school. I can see the peak of the house I grew up in from the parking lot. The AEL program is in the part of the building that used to be the school library, the place where I once unsuccessfully tried out for the school musical. The square tables with the matching cushioned chairs serve as our students’ desks now, but everything else has changed. Most of the bookshelves are gone, walls divide the space into classrooms, and the book check-out station is now the AEL director’s office. The building has changed so much that sometimes I forget I was a student there. An enrollment session gives me a tangible reminder.

Sitting behind the teacher’s desk, I spot a familiar face. I can just make out his profile between the heads of the other students: it is unquestionably the freckled face of my middle school nemesis, Matt. He’d already been held back one year in school before I met him, and he was big for his age. He threw his bulk around like a badge. He was loud and crude but on the whole harmless. I dreaded him not because I thought he would harm me but because I knew he would try to embarrass me.

One afternoon in 7th grade math, I sat chewing a fingernail. He announced loudly, “She’s giving me the finger!” I was mortified because, yes, my middle finger was sticking straight up as I gnawed on it. This is the worst memory I have of him.

At some point he’d broken his leg, and years later he still walked with a limp, the injured leg a lot skinnier than the other one. By high school his over-sized t-shirts had turned black and chains dangled from his cargo shorts. He wasn’t loud anymore but eerily quiet. I don’t remember seeing him past tenth grade.

More than fifteen years later we are back in middle school, and now, I am the teacher.

At the end of the day he comes up to my desk to hand me his paperwork. I say, quickly, “Hey, how are you?”

He recognizes me immediately. “Whoa, how are you?”

“I’m good,” I say. And then the encounter is over.

I haven’t seen him since enrollment. Maybe another opportunity presented itself, a new job or a training program that didn’t require a high school equivalency certificate. Or maybe his plans were overturned by some unforeseen blow. Or was it me that kept him from coming back?

Some students are here by a judge’s order and because their parole officer will check up on them. Others need a high school equivalency certificate to keep their job or because they can’t find a good job without it.

Jeff does not have to be here. It’s the middle of second semester and he could be out riding his motorcycle every Monday and Thursday night instead of learning slope intercepts. He could be at jousting practice (he now does that on Wednesdays) instead of reading about chemical reactions. He has a job and doesn’t need a new one.

He works methodically writing in teeny tiny handwriting, carefully folding down the pages of his notebook after each page is full. For three hours he works, rarely taking breaks or needing help. He is here because he wants to graduate high school before his daughter, whom he has raised by himself. He made a deal with her that if she finished high school, so would he—they would race. When he takes the test in April, he passes, beating her by one month.

Vicki turned fifty years old last year. From a distance she looks like a teenager—tiny build, blond wiry hair, flared jeans, and tight tops. Up close you can see that stress and cigarettes have roughened her face and neck. She’s on medication for ADHD, bipolar, anxiety, and depression. Her hands often shake. Her essays are full of sentences that randomly stop and start.

It’s March, and Vicki has been with us in the mornings since the previous August. She tells me she’s going to court today.

“For your divorce?” I ask.

“No, Robert and I are back together,” she says.

“When did that happen?”

“A few weeks ago,” she says. “I moved back in with him after my mom pulled a gun on me.”

I can feel my face stretching with surprise. “What happened?” I ask.

“I was living with my parents when me and Robert split up,” she begins, “and one night Mom and Dad had been drinking, and I don’t know, I came out of my room and Mom was at the end of the hall waving Dad’s gun around.”

“So, she wasn’t, like, aiming at you?” I say. I feel an arbitrary sense of relief that this gun-wrangling may have been some kind of misunderstanding.

“When she saw me she started screaming at me,” Vicki continues. “Things like, ‘Get the hell out of my house, you leech! You just can’t stop ruining people’s lives!’ And that’s when she started pointing the gun at me. I locked myself in my room and called Robert and then the police.”

I try to imagine Vicki in high school, a petite girl dealing with undiagnosed ADHD and bipolar disease. I wonder if her mom was prone to waving weapons around then.

Vicki tells me she loves me. She says it like best friends say it.

“Love you, too, Vicki,” I say.

Like many students, Michelle feels the need to explain why she didn’t finish high school. Unlike Vicki, she seems to have had a comparatively normal upbringing.

“I wasn’t planning on dropping out. I wasn’t stupid,” she says.

Although she’d gotten pregnant her junior year, she planned to finish high school and then go to college to study nursing. Her friends and family supported her, and when she went to the counselor’s office to sign up for senior year classes, the plan was still intact.

“I told the counselor I didn’t want to take gym until the spring because I was pregnant,” Michelle says. “‘You’re what?’ the counselor says. ‘I’m pregnant,’ I tell her. ‘I want to wait and take gym after I have my baby.’” Michelle has a deer-caught-in-headlights look about her as she tells me this. “She told me I couldn’t sign up for classes if I was pregnant and threw my schedule in the trash.”

One balled-up schedule was a hard enough bump to derail Michelle’s plan. Would the plan have stuck if she’d known how to advocate for herself? Or known that another counselor may have had a different, more compassionate reaction?

Michelle decided to give our program a try after fifteen years working as a certified nursing assistant for minimum wage. She earns her high school equivalency certificate in less than four months.

Ian brings his wife with him to school. He missed our last orientation, but we allow him to enroll because he’s desperate. His wife is pregnant with their second child and he needs a job.

They are both young, but at twenty, he is clearly much younger. His wife hangs on him, arms tied around his waist. She points her face up at him for a kiss. And then another one.

Ian meets her face halfway, but the rest of his body looks ready to spring from her. He hasn’t brought his wife with him, I realize: she has brought him. Tethered to her, he looks like a wild animal. His eyes dart around, and I can easily imagine his lanky limbs loping over fences and across fields.

“You’ll need to go through the orientation process,” I say to Ian.

The young wife reluctantly lets go of him. She leaves, and I take Ian to an empty classroom to take pre-tests and fill out paperwork.

He cannot sit still. His heel pumps at the floor, his hands slap the table twice a second. His eyes dart from his reading test, to the window, to me, to the blank white board, back to his test. “This is easy for me,” he says.

“Good,” I say, “keep going.”

He speaks in a hurry. “I’m even better at math.”

He fidgets through the remainder of the test but completes it in record time. I worry that he rushed through the test without trying, but when I get his scores back, he appears to be right—the test was easy for him. He could improve in a few areas in math, but he should be ready to take the high school equivalency test soon.

Most students who hear this kind of news are visibly relieved. Relieved to know that they’re not as far behind as they thought. Relieved that their goals are within reach.

When I give Ian his good news, it is hard to say how he feels. He stares past my right ear as I’m talking to him and pointing out his scores on the results page. The sudden stillness of his body is disconcerting after watching him in constant motion for several hours. Finally he says, “I don’t want to take the math test until I’m ready. Like really ready.”

“There are a few areas you’ll need to brush up on,” I agree. “But it shouldn’t take you long.”

To help Ian plan for his future, we set up a meeting for him with a representative from the Full Employment Council (FEC), a program that works closely with ours. The representative describes the opportunities waiting for Ian once he passes the high school equivalency test. Ian loves working on cars, so he gets information on a mechanic training program that the FEC will pay for.

But after several months, Ian still doesn’t want to take the high school equivalency test, though he’s ready and our program has money to pay for it. Most students see a high school equivalency certificate as a key that unlocks opportunity. I wonder what a high school equivalency certificate looks like to Ian. A cage? One more tether?

I’m not sure how to encourage him. He doesn’t need the usual help. He knows the multiplication tables; he’s figured out algebra on his own. His reading skills are strong. He doesn’t need me to tell him he’ll do great on the test or to give him test-taking strategies.

I worry that what he needs is less responsibility, time to be a kid. But in the adult education program we specialize in steering students toward more responsibility.

We coax him into signing up for the test. When the day of the test comes, he doesn’t show up to the testing center, and he doesn’t come back to class for a month. We call him. He says he doesn’t have gas money to get to school. We say next time you come, we’ll give you a gas card.

Once he has the gas card, he disappears for another couple of weeks. We call him again, and after a few days his wife answers. She and Ian and their baby had an accident driving to Ohio to help a friend move. We assume he no longer has the gas card to get to school.

A week later Ian comes to class smelling like weed. This is the one thing we, as teachers, are not allowed to overlook. He is told to leave. He does not come back.

The ideal adult education student is somewhere between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-two—people who are experienced enough to fully understand the opportunities a high school equivalency certificate offers but young enough to remember a few things from high school. If this demographic sticks with it, they’ll be done in a matter of months.

But if they’re a single parent, it may take a little longer.

If they have more than three kids, a little longer.

If they work overtime, maybe a little longer.

If their car breaks down and they can’t get a ride to school, longer.

If they have test-taking anxiety, social anxiety, or general anxiety, longer.

If they have to take out a restraining order on their partner, step-brother, cousin, or either parent, even longer.

If they live with any drug users, longer.

If they have ever been hard into drugs themselves, it will take quite a bit longer.

If they relapse, much longer.

If they suspect that their parents, teachers, or friends were right all along and they really aren’t smart, a lot longer.

If they give up, it’ll take…

Longer.

Longer.

Longer.

Tyson carries a skateboard with him to class, along with a large chip on his shoulder. The skateboard isn’t a hobby but his transportation. This is the suburbs: there are no trains or buses. He walks/skateboards from Planet Fitness, a twenty-four-hour gym where he sleeps, to school, a distance of over four miles.

Tyson is a good-looking kid—tall, athletic, a neatly-shaped Afro. His sweatpants fit tightly and he wears his socks pulled up to meet the too-short bottoms of his pant legs. He wears a too-small sweatshirt and carries a too-small backpack. Somehow it works. He looks hip. He has a big white smile, straight teeth, and clear skin. He could have been one of the popular kids in high school.

He doesn’t want help. When I ask him what he’s working on, he jabs at the paper with one finger before going back to scrolling on his phone. I ask if he has any questions, I’m unsure he’s heard me through the ear buds. “No,” he says. But I see that he’s looking up how to calculate percents.

When I see him next class, he’s so desperate, he allows me to help him. He has his writing test in two days and the essay he has just written is one long sentence, the length of the page. I tell him he has the right idea. He has voiced an opinion somewhat related to the essay question. I tell him organization is key on this kind of test. Paragraphs. Periods. I tell him to give me three reasons why he believes his opinion is a strong one. I draw a graphic organizer on the board. I avoid the hamburger-shaped one in favor of one with simple boxes. Together we fill it in.

“Okay, I get it,” he says. But soon he’s stuck trying to turn the three reasons into paragraphs.

We write the essay together.

I try to imagine where he sleeps at the gym. The locker room? The “abs” section? I don’t know what he eats. Powerade and protein bars? I only know he can’t go home. His parents kicked him out for some unknown reason—he doesn’t appear to be on drugs, he hasn’t shown any signs of violent behavior. At times I glimpse a certain attitude, the chip on his shoulder infecting his whole person. But there must have been something that prompted his parents to kick him out. Something more than a bad attitude.

I don’t know what bump in his path landed him in adult education. I only know he is here, and he accepts the packets of worksheets I offer him after class.

“Can I take this pencil?” he asks.

“Yes, take it,” I say. “Take several pencils.”

Brandi Handley earned an MFA degree in creative writing and media arts from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Currently, she teaches English at Park University, a small Liberal Arts college in Parkville, Missouri. Her work has been published in the Laurel Review, Adelaide Literary Magazine, and the Wisconsin Review.