Spaghettification

by Ali Raz

Spaghettification is a scientific word. It refers to the vertical stretching and horizontal compression of objects into long thin shapes (i.e. spaghetti) in a very strong non-homogeneous gravitational field. A black hole would generate such a field, for instance – and not much else. This means that the phenomenon is purely imaginary. It is a hypothetical. Even the name suggests this.

In 2018, researchers at the University of Turku claimed to have witnessed spaghettification. They wrote a paper about it. In this paper, they discussed having ‘seen’, via high-frequency radio waves, the debris of a shattered star. The star had been shattered upon contact with the gravitational field of a black hole. The star had been spaghettified.

In support of this, the researchers offered printed sheets of readings from their radio receivers.

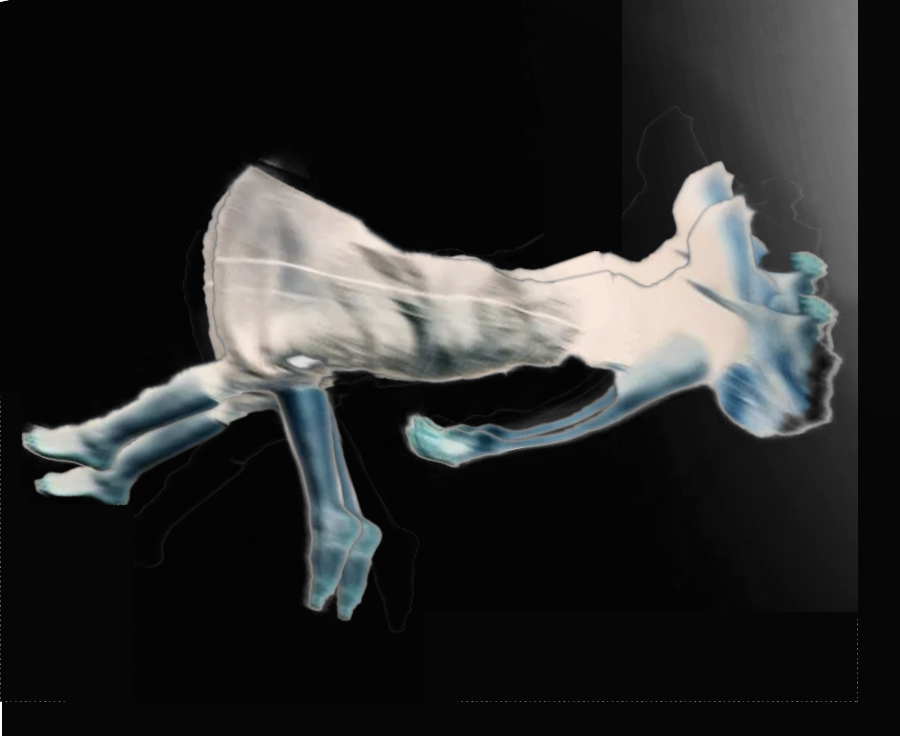

A character is spaghettified in High Life. It happens towards the end. After she is harvested, impregnated, soaked in breast milk, nearly raped, slapped around, and called an insulting name – she offs herself by leaping into a black hole. She doesn’t leap exactly. What she does is, she hijacks a space craft (a small craft which one drives like a go-kart). She cracks the pilot over the head with a spade (the pilot’s brains splay out like intestines) and then makes away with the go-kart spaceship. At first she’s laughing. After all, she is where no one else had been before – an explorer, an adventurer. Then her face begins to change. The mouth is pulled to one side. The cheek to another. She makes grunting noises, like one exposed to great tearing pressure. Then her head explodes.

In the spaceship, they ate soft vegetable soups.

What is space? By rights, there are times when I doubt that it exists.

One gets lonely all alone. One gets lonelier than lymph, a vital fluid no one talks about.

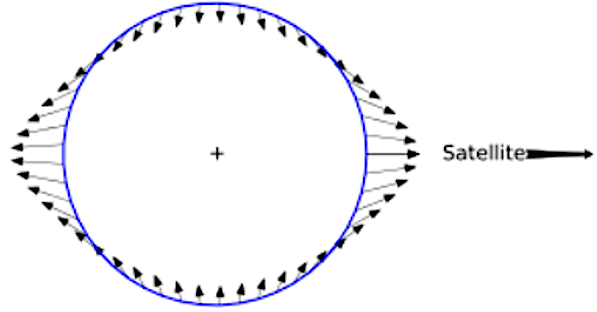

I had been talking to my grandmother. Our conversation was enabled by globe-spanning satellite networks and regimes of power decades (and more) in the making.

Consider a song by Daft Punk. Put on their album RAM.

A violent storm begins, full of lightning and wind.

The visualizations of space in High Life are animated effects. Colored swirls and strobing lights stand in for things that can’t be said. These are cheap effects. They don’t connote (except to designate the unsaid). I much prefer an earlier move. There is a moment, very early in the film, when a character (a man named Monte, whom the others call a monk) drops a spanner from his perch atop the spaceship. He had been performing mechanical repairs, tightening lug nuts and such. Then he knocks, by mistake, a spanner off the side of the ship. He begins to lunge after it – then stops. The spanner falls an infinite fall. Slowly and steady, at one even rate, it falls into the unrelieved black. There is no depth to its fall. No background against which to sense it. It becomes, to the poor stricken character and also to us, as flat as a cardboard cutout, dimensionless as a video game. It is an effect of the mind to derealize what it can’t understand. And it can’t understand an object falling outside of time.

Sensations of scale.

The near-vertigo of scale.

A storm in space would be an invisible, battering, particulate wind.

I would eat an apple in it.

Drop the core down your rotten throat.

The girl I loved would not be here. She would not be anywhere at all.

Not in the gaps of each synapse, virulent and spreading, more motile than bacterial fins.

There are some people – some actors – who are, how should we say this, soaked in such charisma – such personal force – their aura is so reaching and strong – that the hand simply itches to photograph them. Even the camera wants it. The camera itself wants to film them.

Buster Keaton for instance, have you seen him? Getting repeatedly hit on the head with the spinning handle of a well. He doesn’t look like much. He looks like another grain of sand from the desert behind him.

Or Robin Williams. He is a better example. The flickering of that fluid, vital face.

High Life is less frightening than Solaris and less infinite. In its center is a specter of sex; this specter inaugurates, inside the film, another film.

The split of a schizo, hapless structure.

Or the passage, unmarked, of fear between my breath.

My teeth. Your hands.

My teeth, carious. My hands, removed by your sparkling blade.

Ali Raz is co-author, with Vi Khi Nao, of Human Tetris (2020, 11:11 Press), a kooky collection of sex ads. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in the LA Review of Books, The Believer, 3:AM Magazine, Tupelo Quarterly, Firmament, and elsewhere. Her first novella, Alien, comes out in Spring 2022 from 11:11 Press.