Drought

by Jensen Beach

Her great uncle Gerald had died. Amy just finished reading an email that contained a scanned photograph of his obituary clipped by her Aunt Mary Margaret from the Miami Herald. The obituary did not indicate cause of death, but Amy knew that he’d had some heart trouble recently. The news of his death did not surprise her. It also did not make her particularly sad. Still, she printed the clipping, watched the paper skulk from the printer on her desk. Then she held the obituary in her hand, the paper still soft from the ink, and looked at the small grainy black and white picture of Gerald in his service uniform in a way that she thought might indicate her grief if any of her employees happened to walk by her open office door.

The obituary was mainly concerned with Gerald’s love of baseball. He’d also been a Sergeant in the Army, and he operated a bar in Miami Beach for forty years, and he’d left money to the Boys and Girls Club in Westview, which the obituary writer, who was probably Aunt Mary Margaret, seemed somehow equally proud of and disappointed by. Secondary to these topics was Gerald’s dislike for his home state of Wisconsin. He had lived in Miami for more than sixty years, and apart from infrequent visits and his life-long support of the Green Bay Packers, Gerald, the obituary made clear, wanted nothing whatsoever to do with his home.

Amy was curious, frequently, about the notion of home. In her own case, she had tried but failed to move away and was increasingly convinced she’d end her life where it started. There were worse fates. She had been born in the small central valley town where her grandfather had arrived as a migrant in the 1930s from Wisconsin to work first on a dairy farm and then later start a well drilling operation that made him very rich. Her father took over this business when his father died. Amy had grown up, accordingly, in comfort. She went to the state university located fewer than twenty miles to the south in Fresno. Her junior year she had taken an art history course with a required travel component, and she spent two wonderful weeks in Florence and Milan where she visited countless museums and cathedrals. On her flight home she’d vowed to her seatmate, a sickly girl with vision so poor she needed a magnifying glass to read her textbooks, to spend at least the early part of her adult life traveling the world, seeing all that she could.

Not long after making this promise she graduated, summa cum laude, with a degree in accounting. Her mother threw a party for her to celebrate this milestone, and all Amy’s friends came and lingered about the pool and sipped cocktails mixed poorly by the nervous Mardirosian boy, the neighbor from three houses down, whom her mother had hired to play the role of waiter. He even wore a white suit coat. As the party wound down, guests trickling out of the gate on the side of the house as dusk began to settle, her father approached. He gave her a hug and presented her with a business card that read in ornate script: Amy Susanne Murphy, Chief Financial Officer.

“I had this mocked up for you,” he said. He grabbed her forearm at the wrist, a gesture of his she knew well. “Robert will be retiring soon enough. If you put in the effort and the hours, the job is yours when the time comes.” He smiled and leaned in to give her a kiss on her cheek.

Over the years she made it to Mexico a number of times, was proud of the fact that she’d visited the Pacific and Gulf coasts, each frequently. For a short period, she even owned a one-sixteenth share in a condo in a small village outside Cabo, where she visited a few times before selling her share in order to finance a new car. But she never lived anywhere away from home. The house she bought was less than a mile from her parents’ place, and she saw them every day. She never married, but every two years or so managed to entangle herself into a complicated and usually painful affair with a man, often from work, once from church, and increasingly from the internet.

In addition to obituaries, Aunt Mary Margaret frequently sent holiday themed napkins and paper plates in the mail. All of these Amy kept on a shelf in her pantry, never opening a single package. Since Aunt Mary Margaret’s later than normal conversion to email, she had sent the decorative paper goods much less frequently, but the shelf in Amy’s pantry was still overflowing with floral Easter cake plates and glittery New Year’s cocktail napkins.

Apart from a minor car accident in Fresno in which Amy had broken the pinky finger on her left hand, nothing all that tragic had ever happened to her. There were breakups, minor heartbreaks, of course, but nothing out of the ordinary. She did not have a pet that would grow old and die, no children to risk childhood cancers, no husband to betray her singular trust. She worked out three times a week, rarely drank more than a glass or two of wine at a time, did not smoke, and enjoyed skiing and hiking equally. She was in good shape for her thirty-seven years, and had been given a diagnosis of perfect health at her most recent physical. Compare this to her employee Esmeralda, who was obese and could often be heard wheezing on warm days. Amy pitied her. In the last year alone, Esmeralda’s husband had left her for another woman, her son Orlando had been injured in the line of duty in Afghanistan and lost both of his legs, and her youngest daughter had spilled a pot of boiling water on her chest and thighs causing severe burns. Miraculously, Esmeralda had not missed a single day of work to attend to these tragedies. Though of course Amy would have allowed this if Esmeralda had only asked.

She read the obituary again, scanning for information on where to send flowers and curious to see whether she might uncover the architecture of some unspoken family drama regarding where Gerald should be interred. She supposed it would be Miami, where the funeral was to be held and where the address for the funeral home was located. Gerald had lived there so long. He attended Mass at St. Joseph’s, where the services were to take place in three weeks’ time, according to the notice at the bottom of the obituary. But Aunt Mary Margaret was stubborn, and Amy knew her father would do whatever his cousin wanted if this meant avoiding a conflict. Apart from Gerald, all of the Murphy family lived either in California or in Wisconsin. Aunt Mary Margaret might very well insist that Gerald be laid to rest in Wisconsin at the Murphy family plot. In this case, at least, a visit in his honor would not require travel to a place that meant nothing to any of them now that Uncle Gerald was gone.

She’d tried to see Gerald only a year before. There had been a conference in Ft. Lauderdale for small business owners in the construction industry. Amy had arranged to go, hoping to meet other young professionals, perhaps discover some vision of her own for the company and its future under her leadership, new partners perhaps, or more exciting, new markets. The drought had brought some difficult years. Her guilt over the nature of the company had likewise become difficult. A day might be going along just fine when she would be on Facebook and run across one of those time-lapse videos of a lake up north that showed the dramatic effects of the drought on the water levels in the state. On those days, she’d need an extra glass of wine or two at night to find sleep. Her father had been gradually retiring from his position as CEO and Amy was stepping into this new role. He owned the building and most of the equipment and Amy would pay the lease on these items, at once funding her father’s retirement and also purchasing the business and its various holdings from him. They agreed that whatever balance was left by the end of a six-year period would be her inheritance, whether her father had died yet or not.

The day she arrived in Ft. Lauderdale, it was hot and she was sweating through her shirt before she’d even reached the curbside pick-up for the shuttle bus to the rental car facility. The conference was spread across two separate banquet rooms in a hotel near the airport. It rained the first day, a storm that arrived almost simultaneous to her checking in to the hotel. The second day was sunny, but wickedly hot, and Amy did not leave the hotel for longer than the few minutes it took to walk from one building to the other. She spent her evenings in the bar, making awkward small talk and failing to connect with anyone in a meaningful way. By ten-thirty on the second night, whatever vision she may have hoped to discover had been obscured behind the ill-fitting pants and crew cuts and obvious indentations on ring fingers where wedding bands normally sat. She emptied her half-full glass of wine into a potted palmetto by the elevator and went up to her room.

On the third day, the heat broke and she decided to skip the conference events and drive to Miami to see Gerald. She didn’t bother to call him ahead of time. He lived in an assisted living facility in Miami Beach. Aunt Mary Margaret always made sure to send pictures whenever she visited, and Amy felt in some small way that she knew the place, though she herself had not ever been. There was a view of the water from Gerald’s bedroom window.

On I-95 south, she hit traffic and was glad she’d paid the small fee to the rental car company for the toll pass when she saw the sign indicating that she could merge onto the express if she wanted. She did. In no time she was exiting the freeway and driving, by means of several bridges, to the east toward a hazy line of tall buildings on the horizon.

Aunt Mary Margaret frequently wrote emails to Amy about her visits with Uncle Gerald. A major subject of these emails was the traffic problem in Miami Beach. Traffic was “a real nightmare, as you know, and it’s getting worse.” Her emails often affected that casual tone people use to indicate that they have more experience with a thing than might be assumed. But as Amy made her way across the island and experienced the wait at each stop light, the honking horns, the loud music from convertibles stranded in intersections, the motor scooters and throngs of people dragging coolers and beach chairs toward the water, she began to suspect that perhaps Aunt Mary Margaret had not been exaggerating. This made Amy nervous, and so she parked her rental car several blocks away from Uncle Gerald’s place, in the parking lot of a Walgreen’s housed in a building painted so white it hurt her eyes.

In the end traffic was no less complicated for her on foot, though she was more flexible in her options regarding one-way streets and a funny little section where the road had been torn up and large boulders of concrete and asphalt crowded onto the sidewalk directly in front of an erotic art museum. “Come delight!” the sign above the black-windowed front door read.

By midday it was oppressively hot, though thick clouds had begun to crowd the sky and there was a musty smell in the air as if rain was imminent.

Gerald’s apartment building was on the north side of South Beach, two blocks in from the water. It was a wide, six-storied building, decorated on the broad stucco wall above the entry way with a sunrise motif carved into the façade. As she entered the building, Amy tried to remember that she wanted to google art deco architecture when she got back to her hotel.

Inside, the air conditioning was so powerful that she instinctively hugged herself, briskly rubbing her hands up and down her arms. There was an expansive lobby area with a shiny, reflective white tile floor and beyond that an open entrance to what appeared to be a hallway that led back into the building. This was obscured by a long, flowing linen curtain that shrugged in the air that the ceiling fan pushed about the space. Amy approached the reception desk, behind which a young woman was speaking loudly into a phone. When she saw Amy, the woman placed the phone on the desk and said, warmly, “Hello. Can I help you?”

“I’m here to see my uncle,” Amy said.

The woman pushed a guest registry book across the desk to Amy. “You have to sign in,” she said. “Is he expecting you?”

“I’m only in Florida for a couple of days. I thought I’d surprise him.”

“That’s sweet of you. Some of our residents don’t get any visitors.”

Amy began to fill out the information the registry required. As she finished writing her cell phone number and home address, the woman said, “It’s a lot, I know. We’ve had some trouble with visitors. Mostly distant relatives looking for money or else drugs in the medicine cabinet.”

“Of course,” Amy said.

“You wouldn’t believe what people will do to their loved ones,” the woman said.

When Amy had finished with the registry, she replaced the pen and closed the book.

“Do you know your uncle’s apartment number?” the woman asked.

“I’ve never visited before,” Amy said.

The woman opened the registry, scanned with a finger until she reached Amy’s entry and mouthed to herself as she typed into her computer, “Gerald Murphy. Gerald Murphy.”

Amy smiled as she waited, kept her eyes on a large mole on the woman’s chest, below her collar bone.

“He’s in 507,” the woman said. “I’ll let you surprise him. Gerry’s such a sweetie. I’m sure he’ll be happy to see his niece.”

Apartment 507 was the door located closest to the stairwell. She remembered this detail from one of Aunt Mary Margaret’s emails, actually. Aunt Mary Margaret was always delighting in inconsequential details. Amy knocked. She waited for a few seconds and then knocked again. There was a single window in the hallway, a small frosted glass circle framed by a sunset motif, this one made out of metal, perhaps aluminum or chrome. The sunset reflected what little light there was in the hallway brightly. There was still no answer at the door. She had the number right. 507. Perhaps Uncle Gerald was sleeping, or perhaps he’d gone out. It occurred to Amy that she had almost no idea about his day-to-day life.

Downstairs, the woman behind the desk seemed unconcerned that Gerald had not been home. “He’s probably at the beach,” she said when Amy returned. “Most of the residents spend a lot of time at the beach if they’re healthy enough to go out.”

“Right,” Amy said.

“And can you blame them?” the woman said. “It’s so beautiful down here.”

“It’s gorgeous,” Amy said. “Really pretty.”

“I’m from Georgia, but this is home for me. I’m in it for the long haul. I love Miami,” the woman said. She reached for her phone and held it up as if she were about to make a call. “Maybe they’ll even let me have a place here when it’s time to put me out to pasture.” The woman laughed at this.

“That would really be something,” Amy said, surprising herself.

“I’m sure he’ll be home soon, if you want to come back. Take a walk. There’s plenty to do down here.”

“I will,” Amy said. “Thanks.”

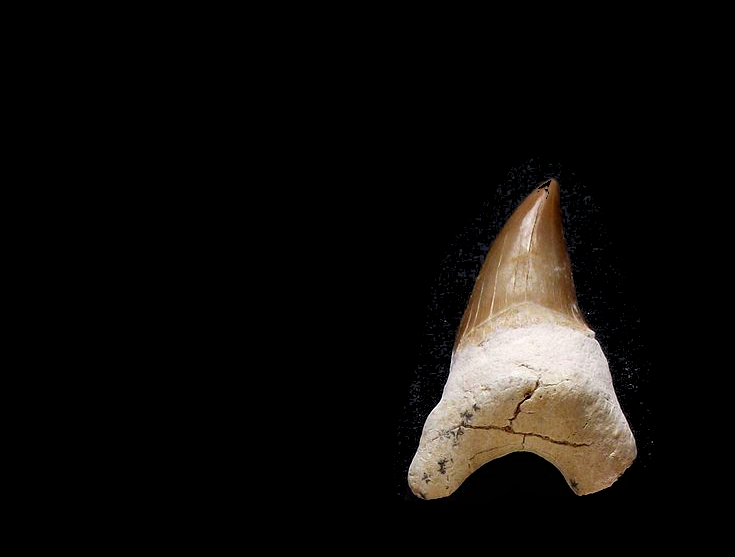

She felt the first rain drops before she’d even made it a block from Uncle Gerald’s place. They were big, thick drops that in no time darkened the sidewalks. And then the wind picked up, and the rain came down heavily and loud, immediately filling the gutters with water and soaking Amy through. She took cover in the first shop she passed, a tourist place with an enormous display of jewelry made with shark teeth—necklaces, earrings, a ridiculous looking headband with the teeth arranged along the top in a way she assumed was meant to suggest a shark’s open mouth.

That was a year ago. In her office, she put Uncle Gerald’s obituary down on her desk. She wondered, briefly, if Aunt Mary Margaret was punishing her for not seeing Uncle Gerald in Florida before he died. It was odd that she hadn’t gotten an email at the least before the obituary was published, or that her father hadn’t called with the news. She didn’t think that anyone had known about her trip to Miami. It was reasonable to travel for business and be unable to make time to visit with distant family. No one would begrudge her that. And no one, as far as she knew, was even aware that she’d tried to see Uncle Gerald but then found herself exhausted from the storm and the little tourist shop and had decided to drive to her hotel and not wait for Uncle Gerald to come back from the beach or wherever he was. But she could not shake the feeling that the timing of the news of his passing had been planned by Aunt Mary Margaret to communicate something to her. The receptionist must have told Uncle Gerald that Amy had visited. And when she didn’t return, Uncle Gerald, offended, must have called Aunt Mary Margaret to tell her.

Amy was a nervous person, a fingernail biter, a fidgeter. She sat at her desk and ran her fingers along the edges of the obituary, pushed the paper back and forth, folded one of the corners, unfolded it. Outside her open office door, her employees passed on their way from one task to another, all of them there for her, and yet not a single one turned to look, no one said hello. She pulled the obituary nearer to her, determined to find some clue as to Aunt Mary Margaret’s motivations. Much loved father, she read, brother, and uncle, Gerald James Murphy passed from this life to his eternal home beside his beloved savior Jesus Christ.

Jensen Beach is the author of two collections of short fiction, most recently Swallowed by the Cold, winner of the 2017 Vermont Book Award. His stories have appeared in A Public Space, The Paris Review, and the New Yorker. He teaches at Northern Vermont University, where he is fiction editor at Green Mountains Review. He lives in Vermont with his children.