The Face is a Wild Land

Cameron Darc

It was one of those Parisian heat waves where hundreds of old people evaporate, leaving their apartments to their children or grandchildren.

When my grandfather died, Maman purchased a one-way ticket for me to attend the funeral. It had been years since I last saw her.

The périphérique traffic snakes in front and behind. Exhaust leaks. Charles De Gaulle airport wavers like a ghost in the rearview. I wake from a premonition in the passenger seat of Maman’s car.

(Men in business suits lie on a black marble floor like a starry sky. IVs keep them alive. The men tell me about luxury. Liars, they never grew up. The mask changes. We are in a dank basement. They are seven-year-old boys who murdered their sleeping fathers. They draw rudimentary animals, make paper flowers, try to offer me ants as gifts.) Relief and sadness compete inside me.

— I need to pee, Maman. I need to pee.

— There’s nowhere to pull off. Maybe there’s an empty bottle somewhere.

I squirm, dig around on the floor.

— I drank too much too fast.

When I find a bottle, I pull down my corduroy shorts and underwear and squat, pressing the glass mouth to the place where it wants out, bare feet on tattered leather. It’s complicated to maneuver, easy to spill. But I have practice. I empty myself. The bottle fills. It still hurts. My urine is unnatural (chrome yellow) saturated as it is with alcohol. I roll down the window and pour it out. I fill the bottle again, empty it. I feel something and look up.

— Dirty bitch. Espèce de connasse.

A man glowers at me from the car next to us, smoking. He spits a long stream into the river of urine on the asphalt between us.

Maman slams the horn and calls him a cunt. I’m seventeen and nonconfrontational. I close my eyes.

This is my old home. The land of Maman’s tongue—which I speak horribly—Maman’s home. We crawl forward in the sea of cars.

Maman doesn’t cry at all. It isn’t a funeral like I imagined. First, we gather at the crematorium with a few members of Maman’s somewhat estranged family that I have never met or don’t remember meeting. Women mostly. One beautiful child with long straight hair. A heavyset teenage boy with yellow teeth who seems to have something missing. Like a too-large child.

When I look at the body of my grandfather, it looks more like cardboard or wax. It is more like looking at a table, a chair, or any other inanimate object. But that isn’t true. His weight and matter are there—but he isn’t anything. He isn’t a table, like a dead tree might be, or meat like an animal. He is not transformed. He is heavy. Death is a weight in the room pulling all the life down. I need to sit. It makes no sense because Maman isn’t crying at all. At first, I think I’m crying for Maman, the receptacle of her unexpressed, muddled feeling. Then I wonder if I’m crying because of the body. The foreign impenetrability of my grandfather’s body. A layer of innocence that I had not known was inside me. Some mind picture in which the dead retained something of the living. So maybe I’m crying for my future dead body.

After the viewing he is cremated. This for some reason I can’t picture. I remember doors shutting. I remember my mother receiving his ashes and putting them in his old car, which for the moment belongs to us. Then we all go to a crummy café and eat gelatinous French fries and drink café crèmes.

— How much?

I cough up a sparrow of smoke, spit feathers. It flies crooked across the alley, disappears. I don’t turn around.

— I’m not a prostitute.

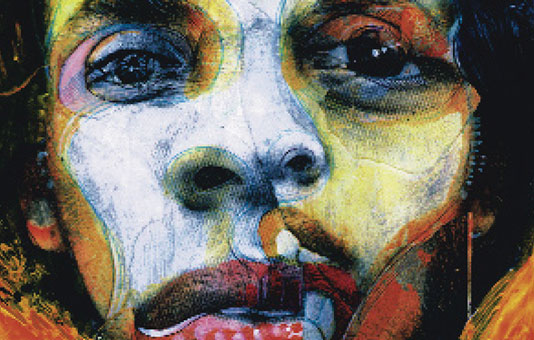

I’m wearing a black dress—for the funeral—and black knee socks and black loafers. I chew on my fifth cigarette, avoiding my mother’s need upstairs. I feel like an old woman. The beauty supply store keeps everything lit up. There’s a mirror on either side of the window display. I have black eyeliner on and mascara and used a lipstick on my cheeks for blush. I learned about my face by seeing it reflected in other’s eyes. It only gives me happiness when I’m alone. The kid watches me from across the alley. He’s gangly. I look at him through the mirror.

— Too bad.

He lights a cigarette.

— Well, how much do you have?

He takes a fold of bills from his pocket and asks me what my accent is. I tell him I’m Polish.

— How long have you been here?

— Two weeks already.

— Come.

Sixth floor. Narrow stairs.

— You go first.

His eyes are on me. I wore big black underwear under my dress. All I have is granny underwear. I try to walk with one leg in front of the other so that my skinny hips dip and sway. I want to cough the whole time but hold back until we get to the top.

— Hush.

He unlocks the door and holds it open. Inside, it’s the smell of loneliness. I recognize it. I open the window, stick my head out. There’s broken glass in the street.

— Sit down, have a drink with me.

I plant myself on the ledge. There are VHS tapes stacked up to the ceiling and two small mattresses. The mattresses form a moat between us.

— You have a pretty ass, he says. Pretty face; pretty ass.

I blow smoke and look at the floor.

— What’s your name?

— Virginie.

He finds two glasses and washes them out in the sink, comes back with a brown bottle.

The feeling of being in a body fills the room. I wait for it to start.

He takes my hand: it looks foreign, a small mouse. Then he grips my thumb between his thumb and forefinger and pulls. His fingers slide off and back around. We’re close. Neither of us looks the other in the eye.

I swallow my drink and take his, swallow that too. The dark fire slides down my throat like a little dragon. He laughs. I lick my lips and look at him and look away. His mouth brushes my cheek. His hands are gigantic butterflies.

— Turn the lights off.

He fumbles the wall behind him. The room goes black except for the windows. There is a pulse I’ve felt only once or twice before. It’s the thing that doesn’t understand the line at the post office, that makes us forget the point of names and what our mothers look like. I pull him down on the mattress and he pulls my underwear down and I open my legs, and he rests his elbows tight under my shoulders. His head hovers above my eyes.

I force my mouth to go lax and take his lips and then his tongue. He tastes like dirt. It’s not unpleasant. I’m a sleeping baby. I open my whole body and go soft, slack. That familiar taste, a headrest, a parked car, crying mouth pressed into a thick wool sweater. Always the same one. I try to forget. I try not to leave my body. This first time, I resist. I let the sweaty mattress climb into my nose. I put my hands on my head. Don’t fly away. Stay. I try to feel the stranger’s chin as he smashes his face into my hair. I see a snake. Maybe it’s him.

I’m not afraid.

Swimming. What was his name? — pulls me under. It feels like a fever. I will think about it when I’m alone. Something stabs me fast then smooth and slow. It doesn’t hurt. When my eyes open, he breathes. My eyes shut. White slashes, headlights on a dark road.

— Was it the stockings?

— Mmmm?

— That made you think I was a whore?

— Mmhm.

I slide my socked feet under his. Our knees touch, separate.

— It was my grandfather’s funeral today.

— My poor girl. Ma pauvre petite pute. (My poor little slut.)

My grandfather swam on his back so he could look up at women’s legs when they walked around the pool. He invented a technique for it. You propel your arms backward like a butterfly.

The boy is breathless rolling off me.

He takes a piss. I hear everything. There’s an open window, more like a square without glass, from the tiny bathroom into the rest of the studio. He’s singing an old song. T’es folle mais je t’aime. T’es folle mais je t’aime. (You’re crazy but I love you.) He turns on the shower.

Blood turning brown between my thighs. I pull my underwear back up. This was my first time.

The money is on the counter by the sink. I fold it inside my fingers. Having done this thing, I can never undo it. And it gets easier.

The blow-up mattress deflates during the night, and I wake up on the ground next to Maman gasping, oblivious under her blanket. I kick her stomach, not hard. A headache knocks on the door, but I won’t let it in. I feel my way to the bathroom, palming the walls.

The pee stings between my legs. A little blood falls into the toilet bowl. The box cutter lies on the tank behind me, and I take it and flick it open and closed. The toilet doesn’t flush.

(It stings inside also. A little burn or hollow rawness in a place that never existed before now. It’s nice to feel something.)

We use the toilet in the bar across the street when it’s more than pee. Yesterday we shared a bag of cherries in the park, staining our shirts. Yesterday we passed a burned-out car.

Afterward we got sick. We went back and forth from the chrome countertop to the toilet. Maman wouldn’t leave the café until she was sure she was done, so we stayed another half an hour. The bartender glared at us.

The best part was watching the John and his date having an awkward café crème, the lime green fish-netting stretched across her tube-topped breasts in the sun.

When we got home, Maman shaved my legs in the bath. She washed my hair with shampoo that smelled like apples. She combed the long tangles out like I was still a child. We left all the windows open and watched the sun sink and the sky go orange then purple. You are mine, Maman said, dressing me in pajamas.

My pad is long and thick. It makes me waddle like I have a diaper on. I put an ice cube in my underwear before lying down. Now I am not hers. I have a secret.

Maman snores so loud she chokes on air. Her eyes open.

— Why are you smiling?

— Péking Duck, I say. I’m hungry.

— T’es folle, toi. Tu sais ?

— Roll over.

Maman stands in her silk robe, her breasts spilling out. I put my mouth to the plastic spigot on the mattress and blow.

— I told you we need to buy a pump for this.

I hold the rubber mouth shut, pull in air, blow again. The mattress inflates a little. Then deflates a little when I let go.

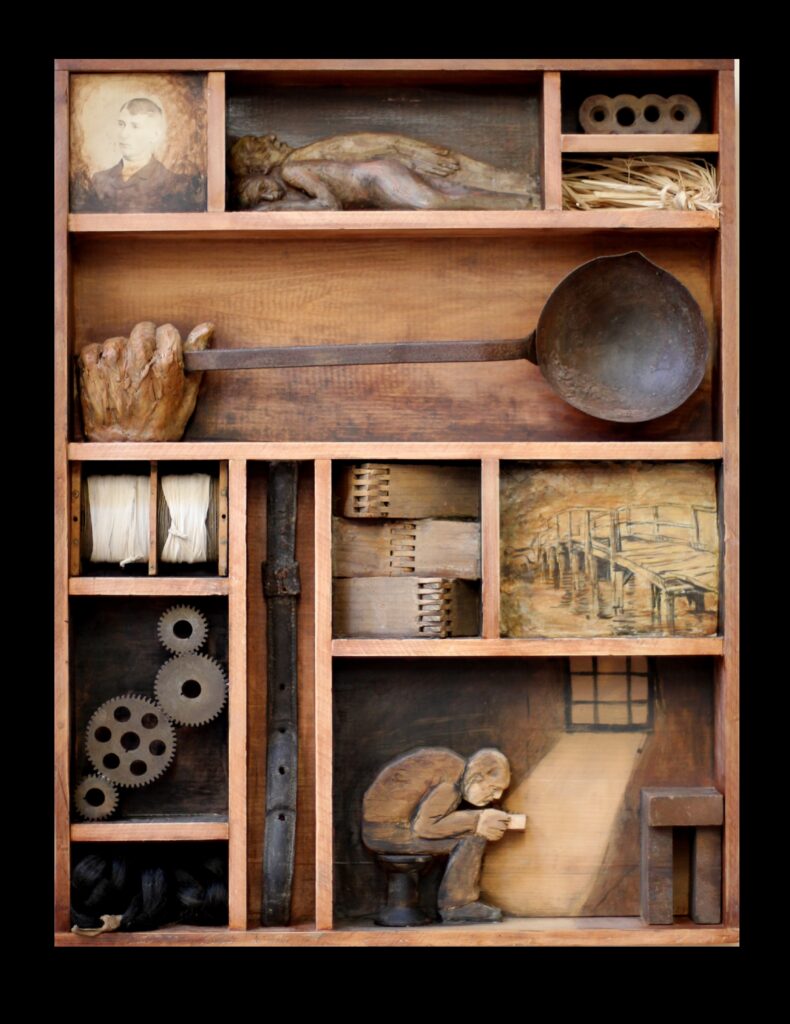

The ashes sit on a shelf. I feel grandfather’s weighty head floating in the room. Maman tells him to move on; There’s nothing to be done here. She says he doesn’t want to move on because he can’t let go of some spiteful feelings and is worried about his dog. Maman doesn’t want the dog.

The windows have sheets instead of curtains. Grandfather blows them around the blue-black room like skirts. A tangled blonde ball floats all the way into the room. It’s not magic. There’s lots of salons on this street. Molted tumbleweeds, red, black, orange, white, roll in the gutters every morning. The women step over them in made-in-China heels. My money rustles on the kitchen counter. If we move too much the air escapes from under us.

— Stop shifting, Maman.

We go with the boy and the dog to spread the remains in a place I choose because Maman is not able to decide what to do. Where did he love being when he was alive? I ask. Somewhere outside? The park, where he took his dog. But when we arrive, it seems like an inappropriate choice. He sat here every day, the boy says, holding the little dog’s leash. The dog seems happy with the boy, but the boy says the dog doesn’t understand what has happened. The dog sits by the door at night, expectant, while the boy watches television.

We empty handfuls near this bench grandpère used to sit on, but the ashes do not disseminate. The grey and white chunks sit in the mud and weeds around the bench, moving among wrappers and dog waste and butts, and blowing into the cobble stones.

Let’s try the trees over there, I say. We scatter the remainder under a group of baby cedars, which only looked a little pretty and bucolic from afar. Up close, they seem temporary. The trees are young. They sit in little round plots of fresh soil, littered with detritus.

I don’t understand why I couldn’t have just kept him, the strange boy says, his little dog sniffing garbage, In a vase in the living room, over the television or something. So that he could stay with us.

But the boy was only a neighbor, and yesterday, it didn’t seem right.

Cameron Darc is earning her MFA at Sarah Lawrence College, where she received a Grace Paley Fellowship in fiction. Her translations from French have appeared in publications by NumeroArt, Le Monte-en-l’air éditions, and Les Requins Marteaux, among others.